|

|

"Mona Mania"

In the canon of Renaissance art, perhaps no image is more recognizable than Leonardo da Vinci's portrait of the wife of a wealthy Florentine silk merchant. Search Google for Mona Lisa and upwards of 4.6 million references appear. Now an icon and starting point for additional artistic expression, the enigmatic image is reproduced, parodied, caricatured, and manipulated in thousands of ways by people all over the world.

For Andreas Jaeggi, artist/sculptor and opera/concert singer located in Basel, Switzerland, the Mona Lisa became "a most recognizable visual witness of past European culture." Using this famous source as a base, he has completed 21 drawings in what will be an on-going series exploring celebrity and its representations. Replacing Leonardo's original mysterious woman with 20th century figures known world-wide, Jaeggi plays with perspective in various forms.

He pushes, prods, teases, and asks us to pay attention not only to the primary subject but to every part of every picture. Interpretation of landscape details – some subtle, some obvious – are significant, particularly Leonardo's use of two different vanishing-point perspectives. The background landscape on the left side of the picture is completely different from that on the right. Jaeggi and others, including Nicolas Pioche of WebMuseum Paris, recognize this device as Leonardo's way of creating two "fantasy" landscapes that are not actually connected.

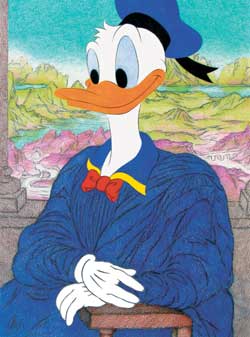

A sense of humor is also a useful accompaniment when viewing Andreas Jaeggi's The Mona Project. The artist's own Mona portrait (Mona Myself) could almost be mistaken for the original – albeit in black-and-white – until the myopic gaze behind a diffusion of eyeglasses sneaks into view. The series' other subjects may be more famous, but the iconic quality of the image remains, even with the literal and figurative comic representations of the selected models. After all, Donald Duck came to life in Walt Disney cartoons. And while the story of Snow White has been in our mythology for generations, the image that most contemporary people associate with this character is the one from Disney's 1938 animated film.

The choice of celebrity and the selection of that celebrity's most recognizable representation are only two of the questions Jaeggi poses to himself in the development of original drawings for The Mona Project. The artist also considers: "Is there a moment in the life of these celebrities when time stops, their image crystallizes, and that's how they are always remembered? At what age should the celebrity be depicted? Is a particular pose important?" And he concludes: "Often, only a very specific image of a celebrity is known to all of us and is truly representative of that person." Like the esteemed lady herself, those images become the icon, and they are the ones Jaeggi chooses for The Mona Project.

The current series began with black-and-white pencil drawings. Color pencil has been used for some of the more recent images, but the artist seems a bit ambivalent about its value. "Color doesn't always add depth and more meaning to a work," says Jaeggi. "The more stylized and restricted choice of expression has often turned out to be the more poignant. Of course, each work will be seen through the eyes of individuals with their own experiences and recollections or connections to the subject."

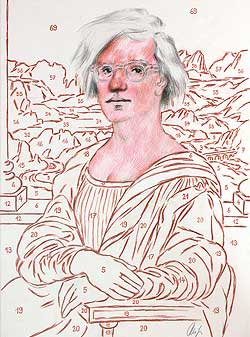

While a work like Mona Teresa may evoke a meditative or philosophical response because of its impressive facial expression, the wink and nod of humor is apparent in other pieces, particularly Mona Warhol. In addition to its combination of black-and-white and color in the head and shoulders, Jaeggi's very Warholian pop-culture reference is a paint-by-numbers landscape and wardrobe.

Jaeggi feels humor is based on "making fun of someone specific or a specific group of people in a specific situation, both geographically and in time. Primarily, it means not taking things too seriously but with a certain personal distance and perspective." Of course, such an attitude presupposes a level of maturity, which may not be present in either the subject or viewer. One person might enjoy the humor while the next may take offense. But, says Jaeggi, "even the most hilarious rendition of a public figure can be a respectful and deeply felt homage."

Leonardo's Mona Lisa has been on both sides of this street: revered and caricatured, celebrated by art historians and deconstructed by popular culture. The original oil painting on poplar wood (77 x 53 cm) is housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Begun in Florence, Italy, in 1503, the portrait is said to have taken three or four years to finish. When Leonardo moved from Italy to France some ten years following its completion, he took the painting with him, where he reportedly sold it to the King, Francois I.

And while Mona Lisa has called the Musee du Louvre in Paris home for the greater part of her life, she is also much traveled. The painting resided at Fontainbleau and Versailles, before settling down at the Louvre after the French Revolution. Even Napoleon was fascinated by the image, installing it in his bedroom at the Tuileries.

But it took until the mid-1800s for the Mona Lisa to find fame in artistic circles, and, eventually around the world. Not all the notoriety was good. In 1911, at the behest of a con man, a Louvre employee stole the painting, and it remained missing for two years. During World War II, the Mona Lisa was stored away from Paris, returning to the Louvre after the Armistice. Following several incidents of vandalism in the late 1950s, the painting was installed behind security glass. Short tours to the United States in the early 1960s and to Tokyo and Moscow in 1974 have since been its only outings. In 2005, the painting was moved to a specially protected hall within the Louvre.

So how did this icon of Renaissance enlightenment become the target of pop culture parody and avant garde art? Many credit Marcel Duchamp, the influential Dadaist, with the first caricature. His 1919 "L.H.O.O.Q." is a cheap postcard-size reproduction sporting a scribbled-on moustache and goatee. The title is actually a crude comment and double entendre: when spoken aloud in French, the letters sound like "Elle a chaud au cul," which translates to "She has a hot ass."

Over the years, Mona Lisa – or her mysterious history – became the subject of songs, stories, books, movies, and all manner of art. Dan Brown's novel "The Da Vinci Code" and the movie of the book released in 2006 are only the most recent examples of how this famous painting has permeated Western culture.

In The Mona Project, Andreas Jaeggi follows both da Vinci and Duchamp, creating portraits enigmatic and outrageous, subtle and challenging. By choosing one of the most recognized paintings on the planet and pairing it with some of the most recognized celebrities of our day, Jaeggi asks us to get involved with the world and its representations. Whether viewers groan or grimace, smile or laugh, Andreas Jaeggi's The Mona Project engages mind and heart – and leaves us all the better for the experience.

By Jill J. Jensen

"The Mona Project"

Art Catalog and Exhibition Event, Basel (Switzerland)

|